Unica Zürn: sexuality in psychosis

It is well described how neurotic children discover the sexual difference. Unica Zürn's Dark Spring offers another kind of testimony, an encounter with sexuality little mediated by the common discourse.

The protagonist confesses a fascination for her father and the masculine body, while that of her mother inspires in her a “deep and insurmountable aversion”. One morning she climbs onto her mother's bed and “is scared by that huge body”. In place of her mother, she faces a conglomeration of intimidating flesh: “The unsatisfied woman hurls herself over the girl, with a humid mouth and a trembling tongue, long like that thing hidden in her brother's pants”.

The absence of a penis in the protagonist's body, unbearable to her, does not - like it usually does in neurosis - become a symbolic lack, which would call for a symbolic solution and allow her to structure her body image, desire and femininity along the lines accepted and prescribed in our culture.

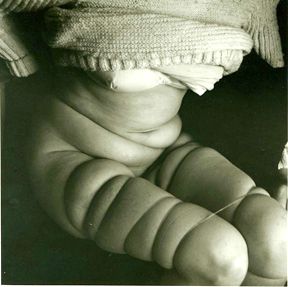

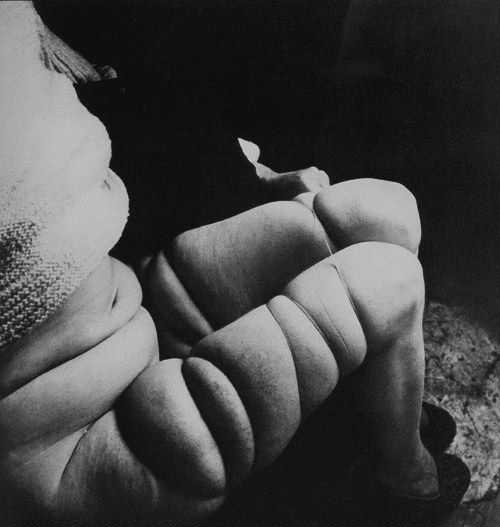

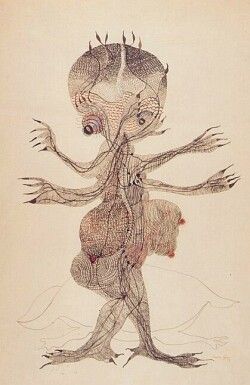

Zürn's drawing, indicative of her disturbed body image

Zürn's drawing, indicative of her disturbed body image

For her, on the contrary, this lack is a literal hole that must be closed, also quite literally. That leads her to search for another, uncommon solution: “She is thinking where to find her own complement. She takes to her bed all hard and long objects… and introduces them between her legs”.

This search for a “complement” and compulsive masturbation, without guilt or shame, do not find any limit. Her first “relation” occurs with a dog: the girl uses the animal's tongue as an instrument of pleasure. Later, she decides to wait for the “remedy” to come from a man – which could seem an Oedipal solution if it were not so literal and unmediated.

In this connection it is curious that the girl falls in love, quite platonically, with an adult stranger. For a while, this love serves as a limit to her sexuality, but soon it turns into real incorporation: the little lover ends up swallowing her beloved's photo.

Without a signification that would come from the common discourse neurotic children draw on, she invents one herself. During an experience of incest with her brother the girl compares their genitals to the wound and the knife. This metaphor seals a previous development: the connection she made between sexual relations and violence. (Well before that, she would fantasise with scenes of torture. “Pain and suffering give her pleasure,” offering a sort of treatment - or at least localisation - for the unbearable and untamed in her body, as well as for her anxiety).

Seemingly, here she manages to give meaning to sexuality and subjectivise it. In this light, one may better understand Zürn's relation with photographer Hans Bellmer, whose tortured doll-model she will eventually become.

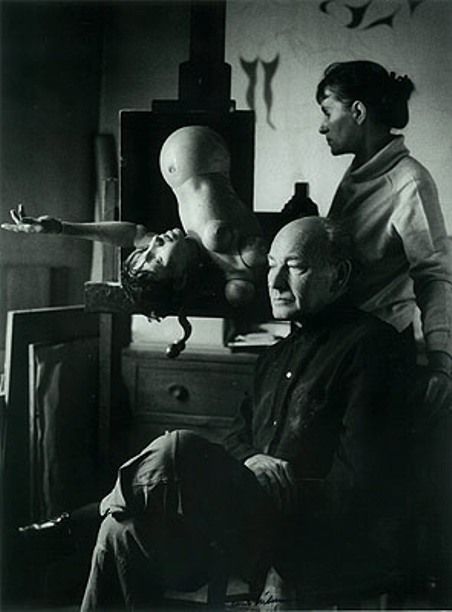

Unica Zürn and Hans Bellmer together in his study

Unica Zürn and Hans Bellmer together in his study

Zürn photographed/tortured by Bellmer

Zürn photographed/tortured by Bellmer