Mary Shelley´s dead mothers

Reading Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein”, one can’t help noticing a multitude of elemental family structures that repeat – or rather impose themselves – throughout the novel at all the levels of its complex narrative frame.

The first element is a couple formed by two siblings, brother and sister, in a very close (and sometimes excessively so) relationship that makes them a sort of doubles for each other. At the level of the narrator, it’s Walton and his sister Margaret, to whom his letters – and, for that matter, the whole narrative – are addressed.

In the story he tells her, there’s, of course, Victor Frankenstein and his sister/lover Elizabeth. (Frankenstein and the monster form another couple of doubles, but that one is based on a different principle). Then, again, in the monster’s story we come across another couple, the “cottagers” Felix and Agatha, whom the reader may at first take for husband and wife – before the true nature of their relationship is revealed and Safie takes on the function of Felix’s lover.

So, at the centre of the novel’s structure, we see three couples of siblings. They all share another important characteristic: they are motherless. Two of the couples live with the father. Safie has no sibling but she also lives with her father and is motherless. Elizabeth, before she was adopted by the Frankensteins, had lost both parents. That already makes 5 dead mothers, and yet, as if it were not enough, the author is compelled to add more.

If we go back to the beginning of the novel, we will remember that Caroline Beaufort, the protagonist’s mother, had also lost hers and lived with her father. When the latter dies, she – somewhat incestuously – marries his friend, Alphonse Frankenstein. Finally, the 7th dead mother belongs to Justine Moritz.

To this surprising collection one should add another missing mother – the monster’s. And, of course, that of the author herself, Mary Woolstonecraft, whose absence seems to constitute the traumatic hole around which the whole novel revolves. However, this absence reveals itself as an excessive presence, that of the dead mother (evident in Victor’s dream): an absence made substance, the unmovable (tomb)stone – der Stein – curiously present in both Woolstonecraft and Frankenstein – which the text conceals at its heart.

My blog in other languages

Client, patient or... Which do you prefer?

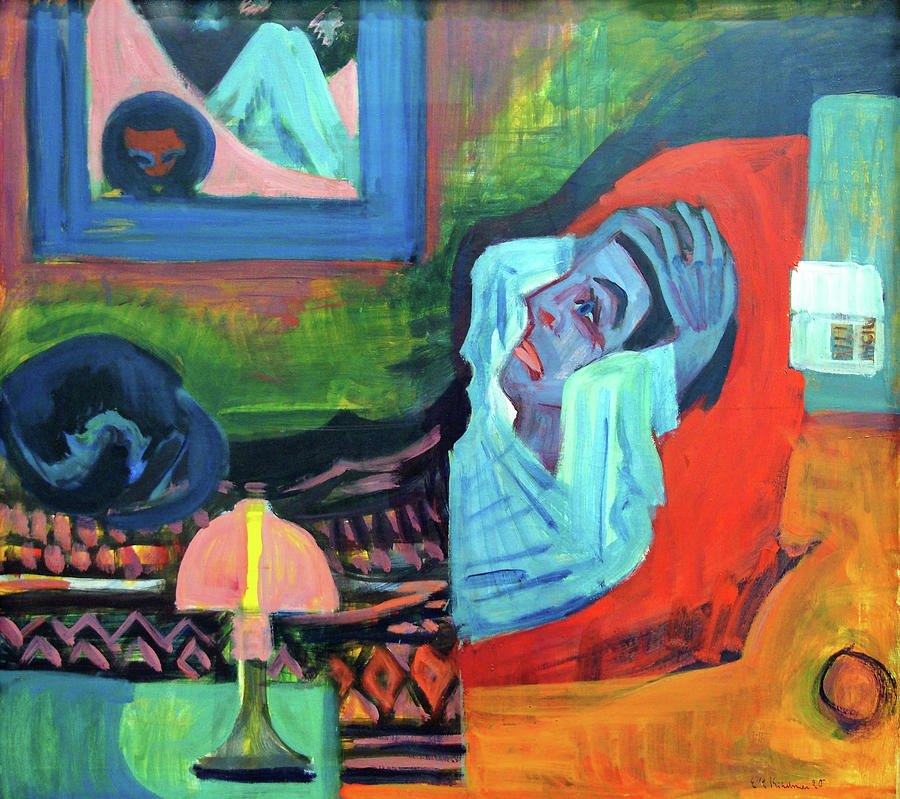

"The Patient" by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Oftentimes psychoanalysts speak of their 'patients'. This one I like and dislike at the same time. On the one hand, this word comes from the Greek 'pathos', it denotes someone who's suffering, which adds the human, subjective dimension missing in 'client'. A patient suffers and so they turn to a therapist for help. Fantastic. But then the medical associations come in and spoil it all: a patient is someone who's ill, they have a disease, they are not 'normal' and thus must be 'cured' by a doctor who knows all about health and illness.

Seen from this perspective, 'patient' may sound pathologising. While 'client' objectified the therapist and therapy itself as something that can be bought, 'patient' objectifies the person seeking help, reducing them to the passive object of medical manipulation. Complementary, it makes the psychoanalyst look like an all-knowing doctor, which they aren't and should never be.

But do we have any other options? In psychoanalysis there's a neologism that apparently eliminates the problems discussed above: 'analysand', or 'analysant(e)' in French. If compared to 'the analysed' / 'l'analysé', it stresses a more active position, that of someone who analyses themselves, thus being the subject, not the object of the process. That would be a great solution indeed, were it not for the fact that the word 'analysand' sounds a bit weird and artificial. It doesn't really exist outside of professional jargon.

So, at the end of the day, one has to choose out of three imperfect words whichever they please and face the music. Now I wonder, if you were going to a psychoanalyst, which of the three would you prefer to be called? Or maybe you can even think of some other options? I'll be happy to hear from you in the comment section below.

Joyce's Eveline, Lacan's jouissance, separation and a fairy tale that can't begin

In this text I'm going to read Joyce's “Eveline” with Lacan. The plot of the short story is very simple. When Eveline's mother – who sacrificed herself for the family – goes mad and dies, the young woman takes her place looking after the household and the younger siblings as well as suffering an occasional beating from her violent father. She works at a shop, too. Everybody's poor, bored and miserable, as it often happens in “Dubliners”. Everybody but the jovial sailor Frank, who proposes Eveline to elope with him to “Buenos Ayres”. She accepts, and yet when they are about to embark the ship, she stops and, paralysed by what may be called an epiphany (or even an onset of madness), stays on the jetty letting the crowd separate her from her beloved:

All the seas of the world tumbled about her heart. He was drawing her into them: he would drown her. She gripped with both hands at the iron railing. "Come!" No! No! No! It was impossible. Her hands clutched the iron in frenzy. Amid the seas she sent a cry of anguish. "Eveline! Evvy!" (...) She set her white face to him, passive, like a helpless animal. Her eyes gave him no sign of love or farewell or recognition.

The central question

is, of course, why on earth doesn't she follow her desire to break

free, why does she stay? This is where three

psychoanalytic notions come in handy. Namely, identification,

separation and jouissance.

Now, while the meaning of the first two is rather intuitive, that of

jouissance

is anything but that.

Lacan uses this

French word, which cannot be simply translated as “enjoyment”, to

refer to a sort of a “dark” satisfaction in suffering, or to that

which lies beyond pleasure – where, when unlimited, it becomes

unbearable and even harmful. In either

case it is something that overwhelms the subject and actually renders

them an object of a blind force acting inside them – “passive, a

helpless animal”. A perfect example is bulimia, where the pleasure

of eating grows into a fit of uncontrollable devouring, with the

subject being virtually eclipsed and possessed by the oral drive.

But let's return to

our protagonist. And to the first notion, identification. One doesn't

have to be Lacan to notice that Eveline is identified with her

mother, who bequeathed her a life identical to hers: an unhappy life

full of Catholic sacrifice (this theme is accentuated by “the print

of the promises made to Blessed Margaret Mary Alacoque” hanging on

the wall) and probably leading to madness.

Eveline chooses to

embrace this future. She can't be separated from her dead mother, her

bully of a father and from the suffering itself. Her place in this

family may be unadvantageous but it's a place she knows all but too

well – it's the only place she has had, and

it gives a meaning to her existence: she

is the object sacrificed to the Other. This, we may suggest, is her

dark satisfaction, a martyr's jouissance

she is

trapped in. And, as psychoanalysis

teaches us, one doesn't let go of their jouissance

easily.

Incidentally, the

impossibility of separation from one's mother is something we also

see in “Ulysses”, in the flashbacks Stephen Dedalus has about his

mother's death:

In a dream, silently, she had come to him, her wasted body within its graveclothes (...) Her glazing eyes, staring out of death, to shake and bend my soul. On

me alone. (...)

Her eyes on me to strike me down. (…) No, mother! Let me be and let me live.

That

is, Stephen feels his dead mother doesn't

let him live. She

draws him towards death. They won't be separated. A few pages later

we will find some telling and almost disturbingly physical images of

a union that can't be broken:

Yet someone had loved him, borne him in her arms and in her heart. But for her the race of the world would have trampled him under foot, a squashed boneless snail. She had loved his weak watery blood drained from her own. Was that then real? The only true thing in life? (…) What has she in the bag? A misbirth with a trailing navelcord, hushed in ruddy wool. The cords of all link back, strandentwining cable of all flesh.

It's curious, too, that in these passages the child is seen both as part of his mother's body and as her object, a helpless little repulsive thing at her mercy. This being the object of mother's jouissance and this lack of separation are quite common in psychotic subjects – and Joyce is no exception.

In “Eveline”, this link with the mother also manifests itself in the enigmatic words the heroine remembers her mother utter on her deathbed, Derevaun Seraun! Derevaun Seraun! As Jim LeBlanc (1998) suggests, these words might be “corrupt Gaelic for 'the end of pleasure is pain'”, as well as for “I have been there, you should go there”, or, surprisingly enough, they could mean “true desire/air/climate (is) free desire/air/climate”.

Be it as it may, this phrase has to do with jouissance (“the end of pleasure is pain”) or the imperative to follow either her mother's path (“you should go there”) or “free desire” (which would be the path neither Eveline nor her mother followed). However, even more interesting is the protagonist's response to the irruption of this memory:

She stood up in a sudden impulse of terror. Escape! She must escape! Frank would save her. He would give her life, perhaps love, too. But she wanted to live. Why should she be unhappy?

That is, these words must symbolise Eveline's being tied and trapped in the repetition of her mother's life. We could even say that they are inscribed at the very core of her identification, a fatal union expressed in the mysterios private language of her mother's – her mother tongue – as opposed to the intelligible common language that integrates the subject into an ordered world shared with others.

Finally, it's not without significance that in the passage quoted above the identification with her mother is opposed to life, as if to act upon it meant to die. It's hardly a coincidence that the owner of the shop Eveline works at asks her to “look lively”. Between life and death, Evelyn clearly gravitates towards the latter. And, indeed, according to Lacan, whereas desire makes one alive, jouissance mortifies. But there is no desire without separation, desire is produced by a lack, and in particular by a lack of jouissance. Which would also be why Eveline can't truly love her sailor: her heart is engaged elsewhere.

In his famous research into folklore, Vladimir Propp points out that for a fairy tale to begin, someone has to leave – either the protagonist has to leave their family or a family member has to leave them. That is, for something to happen, a separation should take place. For this very reason, Eveline's tale is a fairy tale that doesn't even begin. The prince is abandoned and there will be no miracles or magic gifts – the enchanted heroine remains in the "paralysis" Joyce aimed to portray.

On the other hand, were Eveline a clinical case, one would think twice before encouraging her to follow Frank to the other end of the ocean. Such a radical separation from everything that, however poorly, sustained her existence, could actually bring about a real breakdown. Psychoanalysis shows that it may be risky to take a patient's symptom away from them: often it is the very thing that keeps them afloat.

Unica Zürn: sexuality in psychosis

It is well described how neurotic children discover the sexual difference. Unica Zürn's Dark Spring offers another kind of testimony, an encounter with sexuality little mediated by the common discourse.

The protagonist confesses a fascination for her father and the masculine body, while that of her mother inspires in her a “deep and insurmountable aversion”. One morning she climbs onto her mother's bed and “is scared by that huge body”. In place of her mother, she faces a conglomeration of intimidating flesh: “The unsatisfied woman hurls herself over the girl, with a humid mouth and a trembling tongue, long like that thing hidden in her brother's pants”.

The absence of a penis in the protagonist's body, unbearable to her, does not - like it usually does in neurosis - become a symbolic lack, which would call for a symbolic solution and allow her to structure her body image, desire and femininity along the lines accepted and prescribed in our culture.

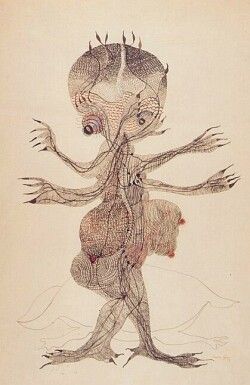

Zürn's drawing, indicative of her disturbed body image

Zürn's drawing, indicative of her disturbed body image

For her, on the contrary, this lack is a literal hole that must be closed, also quite literally. That leads her to search for another, uncommon solution: “She is thinking where to find her own complement. She takes to her bed all hard and long objects… and introduces them between her legs”.

This search for a “complement” and compulsive masturbation, without guilt or shame, do not find any limit. Her first “relation” occurs with a dog: the girl uses the animal's tongue as an instrument of pleasure. Later, she decides to wait for the “remedy” to come from a man – which could seem an Oedipal solution if it were not so literal and unmediated.

In this connection it is curious that the girl falls in love, quite platonically, with an adult stranger. For a while, this love serves as a limit to her sexuality, but soon it turns into real incorporation: the little lover ends up swallowing her beloved's photo.

Without a signification that would come from the common discourse neurotic children draw on, she invents one herself. During an experience of incest with her brother the girl compares their genitals to the wound and the knife. This metaphor seals a previous development: the connection she made between sexual relations and violence. (Well before that, she would fantasise with scenes of torture. “Pain and suffering give her pleasure,” offering a sort of treatment - or at least localisation - for the unbearable and untamed in her body, as well as for her anxiety).

Seemingly, here she manages to give meaning to sexuality and subjectivise it. In this light, one may better understand Zürn's relation with photographer Hans Bellmer, whose tortured doll-model she will eventually become.

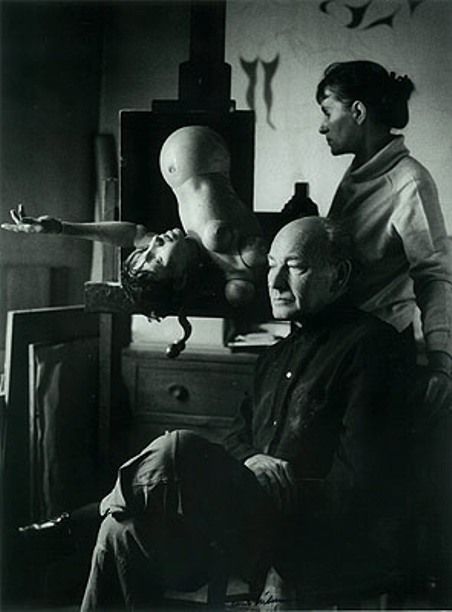

Unica Zürn and Hans Bellmer together in his study

Unica Zürn and Hans Bellmer together in his study

Zürn photographed/tortured by Bellmer

Zürn photographed/tortured by Bellmer